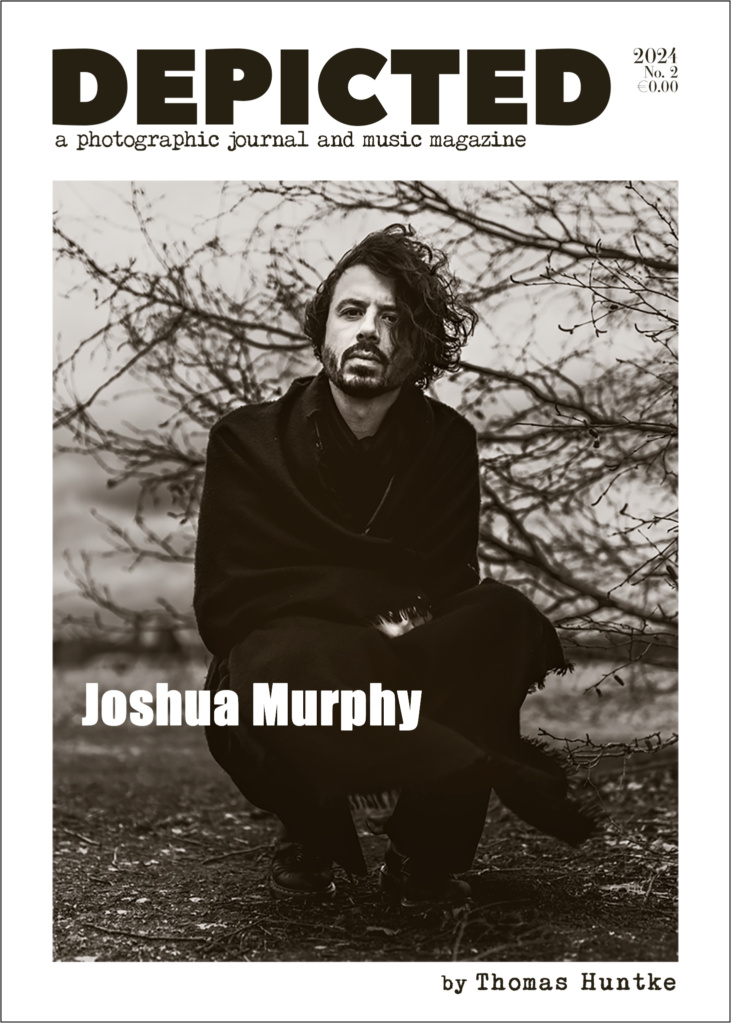

You are from Australia. How did you grow up there?

I was born in what is known as rural Australia, about 100 kilometres outside of Melbourne in a place called Tourello. There is nothing there. I was raised on a farm, one hour outside of Melbourne. This used to be a gold mining area in the 1850s. Before there were only farms and then they found gold and all the miners moved down, Welsh miners, Chinese miners. A few hundred thousand people were living in the proximity at the time around 1850-1870. There were these little towns with great beautiful infrastructures there, big churches, big libraries, big schools. And then the gold dried up and everybody moved away.

So I grew up in this place, really, there was no one there, just me and my family and a few other farms close by. And then there are all those tiny little towns scattered around there with 500 people living there. But they used to be these gold rush towns. They are quite beautiful and historically interesting. The first Mad Max film was shot there.

I was born to an Australian father and an Italian mother. My mother moved out to Australia when she was young, and they met at university. In the 80s it was very rural and very unforgiving, it was a kind of isolated, racist place. So, I was always raised between these two worlds, my Italian side and my Australian side. I always had a very big interest in Europe. When I was six or seven we lived in Italy for a year, that was my first time in Europe. My mother is from a place called Anzio, it is about 50 km south of Rome. I went to school in a place called Castelli International School.

Then we moved back to Australia. When I got older I was touring in bands a lot, up and down the coast, but Australia is a very unforgiving place to tour. There were many times when you would wake up in Victoria, which is in the Melbourne area and drive 1000 km to Sydney to get there for soundcheck at five o’clock and then play the show, sleep a few hours and then drive back to Melbourne another 1000 km to play the next night. Touring like this is brutal. When you are 18 or 23 it’s fine, but after a while, it was not something I wanted to do forever.

I always had this interest in Europe. So when I was 27 I was doing a tour with a band that finished in Berlin. And then I just stayed. It’s as simple as that. I had been here many times, I liked the city and I just didn’t want to go back to Australia and continue that struggle. There are a lot of great musicians there and they really struggle a lot. There is no money, there is the lack of the infrastructure of an industry. Especially for those mid-level 200 – 500 capacity venues that we love so much. While here you can drive 2-3 hours and play again and again. I hear that things are changing because Australia has a lot of rural areas, a lot of small towns which are slowly becoming cities and have these beautiful old theatres.

So that’s how I grew up, riding horses and racing motorbikes on a sheep farm.

Do you miss the country life sometimes?

Not yet. I do have a real affinity for the country. There is something that gets in you, those open spaces, the silence, the beauty.

And you know everybody. I Berlin you don’t even know your neighbor.

That’s true. So, do I miss it? Not enough to go back. I’m not such a nostalgic person. I love the place I grew up in, I was happy to grow up there, but no, I don’t miss it.

When you came to Berlin, how was it for you? What were your first impressions?

I remember instantly realizing that there was a real respect for social issues and for the right to live and for the right to live at a fair price and in a fair way. This was something that really took me instantly. I remember if friends were putting on concerts and there were bars that I was going to and the beers at this time were like 1,50€ or something. And I remember asking a friend of mine who was running the bar: “Why do sell it for 1,50€”? Coming from a very capitalistic place like Australia where everyone’s trying to get as much as they can. And he said to me: “Why should it be more?”. It was this simple answer, it really floored me. It stuck with me, and it was something that I’ll never forget. It was so simple in the way that he phrased it, it was beautiful.

And then this started to shape my view on Berlin, and all the shows, and the fact of shows being cheap. The people then in turn were supporting art and culture in going to all these shows again and again. People like yourself. I have so many friends that I only know from concerts, and they would be there every night again and again. And paying a fair price and being involved in something, this ability to be able to live. And to be able to enjoy and to be able to create something which also, I realized, comes from the things we were speaking about earlier, like the proximity of cities and the infrastructure that exists. That is just not possible in Australia, and this is something that I still love about Europe. It’s obviously changing, it’s getting more and more expensive.

The beer is not 1,50€ anymore.

No, It’s not 1,50€ anymore! [laughs]

On Friday, I was at Supamolly, I haven’t been there for ages, and I ordered a red wine and the guy took a Coca-Cola glass and poured it full of red wine and asked me for 2,50€.

Well, that’s perfect! These things still exist in this city, and I believe that’s a clear decision from the people running the venues and the people running the institutions. They could charge more, and the fact that they don’t is a conscious decision, to do that in order to not just see the opportunity or not just see the singular opportunity of monetary value. Because there’s an opportunity in making people feel welcome in your space as well. And this has a flow-on effect and resonates with the bands and with the public and with the community, if I can use that word, that is created as a result. This was the biggest thing and remains to be the biggest thing that struck me about Europe and Berlin in particular.

But it has changed a lot and I asked myself what will be in 10 years? You know, everything has become so much more expensive. What will be in another 10 years? Will people still be able to go to shows and have drinks there? How do you feel about it?

I don’t know, it’s a good question. I have asked that myself and I think that I just keep coming back to the answer that it’s still better than most capital cities. Well, then, all capital cities. I’m not from here, I’m not from Berlin and I’m not even from Germany. So, it would be hypocritical for me to say that things are changing for the worse as a result of more and more people. Which is probably one of the causes, to be realistic. But what I choose to focus on is that I still believe that there is this fundamental kind of social justice sentiment to the city. And this doesn’t exist in London, this doesn’t exist in Paris, Rome, New York or Melbourne.

The people of Berlin keep surprising me, so I wouldn’t write off the city yet. I wouldn’t say that it’s going to go the same way that all other cities have. It’s definitely becoming harder; it’s definitely becoming more expensive but I still feel that the city and the people will find a way to not end up exactly like all other places.

So, when you came here, did you continue making music? I first got to know that you were a musician when you were recording this album with Crime & The City Solution.

No, when I came, I stopped. I had been touring and playing in bands since I was 14 and when I arrived in Berlin, I was 27 and I really needed a break from touring and playing. Then I met Nico Defawe from Urban Spree, and I joined up with him and started to curate concerts and being within the venue involved in a creative way.

I thought that I would only need a few year’s break in order to get back my desire to play again. But it ended up being a lot longer. It was almost the better part of a decade, before I really got the desire to play again. I just spent that decade working with Nico and Catherine just hosting bands, and that became my love. For many years. And this is also a result of the things that I was speaking about before, this idea to create some sort of community and see people play and host them. Nico had a big influence on me because he really comes with this idea of hosting people and hosting bands. This was something that I hadn’t encountered before even though I had been touring for so many years. There was a sound guy, there was a light guy, there was a bartender, but there was no host in a sense, and this was something that fascinated me. It was a desire that Nico has and that he kind of instilled in me to host people and to orchestrate a beautiful evening, a synergy. To be the glue in a way, if you can, that ties everything together.

I just spent the better part of a decade existing in that. Watching great, great bands 5-6 nights a week, again and again and slowly my view on music changed. I changed. I got older the type of music that I wanted to create changed. Then I guess when the pandemic hit, I started to create. I had more time and I started to meet up with an old friend that I had met when I first moved to Berlin named Martin J. Fiedler. He’s a record producer. And he invited me around to his house and we started sitting at his baby grand piano just for days and hours on end. I would show him sketches that I was slowly starting to work on. He’s a very kind man and a very patient man. And over the course of about a year, we would just meet and have coffee and I would show him my sketches and he would help push me in the right direction and give me advice. Eventually he became the producer of the music that I was starting to create.

Then I slowly, just very, very slowly, started to dip my feet back into playing again and very slowly that desire to create came back and that desire to finish something.

I realized that it was time to play again when I started playing guitar at home for the sake of playing guitar. This was something that had left me. Which was hard for many years because I grew up playing guitar. I used to play obsessively for many hours a day. There were periods when I was playing 8 hours a day for years at a time. And that had somehow slipped away, and when I noticed that I was playing guitar at home, just for enjoyment, that was when I realized that I wanted to start making music again. I was ready to present something and go back out on the road.

Then me and Martin worked on this EP, “Lowlands” which came out last year. Then Martin was producing the record for Crime & The City Solution and the guitar player left throughout the recording process. They had most of the structures down for the songs, but he then invited me in to add some extra flourishes on top.

They are also from Australia; did you know them before?

No, I didn’t. So, the band is, I mean, obviously it’s a revolving cast of members this band. It’s Simon Bonney, the singer and his wife Bronwyn Adams. Bronwyn’s been there since almost the beginning, and it’s been the two of them. Then with a revolving cast, even on this record, it’s still a revolving cast of members. Like the bass player, Frederic Lyenn he joined them lately. He was Mark Lanegan’s bass player and Simon and Bronwyn had not been playing for many years and they went on tour supporting Mark and that’s where they met Frederic. Sadly, Mark passed away and this was at the time when they had started to make the record.

So, Frederic joined, and I think that he’s a wonderful multi-instrumentalist. He played a lot of the guitars as well on the record. It was a wonderful project. Sometimes we’re not even sure who played the guitar on which song. In the end there’s three guitar players on the record in different parts and it’s kind of all been chopped up. That was a very fun project.

Talking about multi-instrumentalists: In almost every interview I read about you, the second sentence is that you are a multi-instrumentalist. So now I want at least a list of 10 instruments. [laughs]

It’s funny, I’ve been waiting for this question. “Lowlands” was my first release under my own name and I’m predominantly a guitar player. Always have been. Then when we were making the record, I proposed the idea to do a record without guitar. There’s one song with some acoustic guitar in there, which is just kind of holding the whole thing together, strumming some chords. But predominantly there’s no guitar on the record. I was playing piano and synth and composing a lot of the string parts and stuff.

When the time came to do the PR for the record, I was speaking with the publicist about writing a bio and I had nothing. It was my first release, so I had nothing behind my name. So, we were talking about what to say about this record. I was explaining the process to them and the multi-instrumentalist thing came up. They were asking me what instruments I play now. I do play a lot of instruments, but I’m predominantly a guitar player, but I also play bass, banjo, mandolin, percussion, piano and synthesizers. Then I’m a singer, which I guess is also an instrument. But to be perfectly honest, I don’t think of myself as a multi-instrumentalist. This was something that was, you could say, cooked up by the PR.

I was also composing the strings, or some of the strings. Jonathan Dreyfus, who joined for the record, composed a lot of the string arrangements beautifully, I must add. So, they coined this phrase and said that we must focus on this multi-instrumentalist aspect. I remember at the time when they said it, I thought I wonder if this is going to become a thing that gets picked up and just thrown around constantly. And of course, it has.

And then you went on tour. How was that to be back on tour after almost a decade, being a decade older?

That’s exactly the first answer that I was going to give, I am a decade older. And that was clear, I must say. So, on the tour I was doing both the support and the headliner. In Crime &The City Solution I was playing guitar and some synthesizers and I had a sampler that I had recorded some stuff into, also for my solo show. And then of course, doing two setups each night and doing two shows each night. In the end it was 46 shows in 30 days, including off days. And to be honest, it was wonderful. It was wonderful to be back on the road and play.

I think that when we go back out again, I will try to prepare my body a little bit more. You can be fit but there’s a thing that people call gig fit, which you can only get from touring constantly. I noticed that there was obviously a lack of fitness. But I love to be back on the road. I love to be playing songs, I love to meet people. As I was speaking before, about spending a lot of time hosting people and trying to create places, I loved to step into other people’s worlds, to meet the promoters, meet the crew, the local techs and this was a really big joy for me.

Yes, I think so. Because you also have the perspective of being a host and you can see how all the other venues host you and learn from it. This must be very interesting.

Exactly. That was very interesting. And I have to say that most people are very kind. And they believe in what they’re doing, which is just something that I think is just very cool. I admire that, because you of course notice that when you’re doing a show, you have the venue and the venue is an established place. But you also have the promoter that comes into the venue and a lot of the promoters are doing this as a side hustle. And in some cases they lose money, as a result, in order to facilitate art for their city and for the people and for their lives. This is something that I admire greatly. To be out there and meeting these people and making connections with them and speaking with them after the show.

And especially in instances where they may have lost money and when they’re still just very happy and remaining human. Just being happy about the fact that people had a good time, and that they themselves had a good time and that they were proud of being able to facilitate this and put on the show. That was a big plus about touring. And that was not something that I had the perspective of in the past, it wasn’t something that I was aware of. Also, then the other side of it, the public, the punters, as we say in Australia. Everyone was very cool, everyone was very kind.

As I was saying, I did the support and my music is very slow and it requires silence and attention. It’s not just that it requires silence, but it requires silence as an instrument, for the music to resonate within that silence. And within that room. It’s just as important. Everyone was very attentive and quiet and present, which was really beautiful.

Crime & The City Solution was founded in 1977, so there is a large range of fans that are different ages. So, there was also a large group of people in their 50s plus and there were a lot of younger people as well. I assume that they had kind of researched where they were going, beforehand, and checked out who the support band was. So, they had realized that I was playing in both bands. This is an assumption, though if true, through this they gave me the space to play and were very attentive and kind. That was a real gift. I spoke to a lot of great, cool people after the shows who were really happy to be there. I guess a lot of them probably used to go to a lot of shows, perhaps a percentage of them don’t do it so much anymore, with children and so forth. There was this really beautiful sentiment of celebration in the room.

Some years ago, the news broke that Urban Spree will be closed and that it will be torn down for the construction of some corporate buildings. But since then, not much has happened, so maybe you can give a little update on how the situations is. Also, how did you hear about the first time and how did you feel about it? It must have been a shock.

The news of potential closure has now become such a long, drawn-out process. We first got the news five years ago, of imminent closure. But even when the place started 10 years ago it was always negotiated that it would be there for a limited amount of time because the place was always going to be redeveloped. This was an integral part of how we ran the place from its inception, when you know that you’re there for a limited amount of time, you do things differently and perhaps you celebrate each moment more.

You do things more recklessly in, in a good way. That was always, to be honest, a good thing knowing that this was not going to be forever. It was always a celebration to see what we could create within this old, derelict building, that’s not beautiful. The place is cold in winter, it is hot in summer. This is not here forever, so let’s just completely focus on creating Art and celebration in this moment rather than aesthetic beauty. This was always a large part of the spirit of the place.

Then around five years ago we were faced with the fact that there was only a few years left, which was, of course, sad. But it was something that we were always prepared for. Nico had started another project, the Urban Boat, with his wife Aelxia back in France. So, he was now split between the two projects, moving back and forth between Urban Spree and the boat. Also the original operational manager Frederic Wickström had left to move to Leipzig. And this was all in the face of the fact that we knew that this was coming to an end. But we continued running it and continued doing shows. Then we got to 2019, where we thought we had one year left and that in 2020 we were out. And then the pandemic hit…

Then things started to change with the owners of the space they started to offer extensions on the lease, and they started to be a little bit more quiet about the redevelopment of the place. And the only thing that I can assume, is that things got harder for them as well as it did for everybody. Perhaps the cost of building materials, perhaps the bureaucracy that is involved with redeveloping a place of that size. Because they’re redeveloping the whole RAW-Gelände. And all of that tied up within the midst of a pandemic, obviously becomes harder and harder. So, things continued to get extended and now the pandemic is behind us and it’s 2024. Which is years after we thought that we were gone. All we can see on the horizon for now is that the feeling of imminent closure seems to be gone for now.

It might come back, that from one year to the next they say: No, that’s it. You’re done. But we now seem to be back from the pandemic, the venue is open, the people are back. I might be wrong, but I don’t see any imminent closure coming anytime soon.

(C) DEPICTED Magazine March 2024

No usage of the photos without permission.

Read on:

Interview with Sara from MESSA / DEPICTED #1

Your tour with SABBATH ASSEMBLY has just finished. When you come back home after such a long tour, is it a relief or are you rather sad? Both of them. Being on tour is as much fun, and as......

Interview with Toni from (Dolch) / DEPICTED #1

ENNIO MORRICONE – “Once Upon A Time In The West” [from the 7”, 1968 / German: “Spiel mir das Lied vom Tod”] This is one of my first childhood memories: There is a man hanging on the gallows, standing on......

Interview with Justin Sullivan from NEW MODEL ARMY / DEPICTED #1

Last night you played at a festival dedicated to world peace. Did you ever believe in such a thing? I read somewhere that some historians did some research. In the total of human history there had been a period of......

Interview with Alex Ithymia from SUNSHINE & LOLLIPOPS and BHNP / DEPICTED #1

So let’s switch to English now. I am very curious about your accent. It’s horrible. Ever heard THE SCORPIONS speak English? I am slightly better than Rudolf, but not much [laughs]. It’s a bit strange to talk to a......

Interview with Shazzula from Wolvennest / DEPICTED #1

Shazzula is an interesting name. Where did you find the inspiration for it, and does it have a meaning? Well, in the early days of Napster, I spent some time there exchanging musical interests with some people. Everyone was......

Interview with Marcelo Aguirre from EVIL SPIRIT / DEPICTED #1

You are one of the people with the most diverse taste in music that I know. From metal to jazz to experimental and electronic music, you listen to everything. Was it like this from the beginning, or did it......

Photoshoot with LAUREN RUTH WARD/ DEPICTED #1

Unfortunately there was no time to do an interview, so this is a photo gallery feature. Enjoy. See the complete set of photos with Lauren in fullpage size in the print issue of DEPICTED. Get your copy......

Interview with Malte from NECROS CHRISTOS and SIJJIN / DEPICTED #1

The era of NECROS CHRISTOS is coming to an end. You released the last album and now you are playing the last concerts. Have you already reflected on a personal conclusion to this project? What were your highlights and......

Interview with EVILYN FRANTIC / DEPICTED #1

I heard this story once, that when you started your life as an artist, you ran away with the circus. Is this true, or is it just a legend? No, it is very true. I kind of ran away......

Interview with Lupus Lindemann (KADAVAR) / DEPICTED MAGAZINE Oct 2023

What do you want to talk about? Difficult question… In any case, I have never started an interview this way. [laughs] Normally you have your answers laid out already, and you know what you want to say. You meander......

Interview with Yvonne Ducksworth (TREEDEON) / DEPICTED MAGAZINE Nov 2023

What do you want to talk about? I do have one thing that I do want to get right out there. Something that obviously has to be said. Everybody should wake up and start doing their part, no......

Interview with S. M. from E-L-R / DEPICTED MAGAZINE Jan 2024

What do you want to talk about? This is a difficult question. A very open one. What´s on your mind these days? A lot. The world-weariness is very present with me. On the one hand it’s the ongoing......

Interview with Joshua Murphy | April 2024

You are from Australia. How did you grow up there? I was born in what is known as rural Australia, about 100 kilometres outside of Melbourne in a place called Tourello. There is nothing there. I was raised......

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.